New Amsterdam: “What’s in a Name”

Dutch-American Stories: #3

by Jaap Jacobs

The small colonial town that the Dutch founded in North America was called New Amsterdam. We now know it as New York City. The story of how the name evolved has many twists and turns and is, in fact, a tale of war and peace.

New Amsterdam was the talk of the town in 1953, as New York City commemorated the 300th anniversary of its city charter. Pomp and circumstance were the order of the day and a special stamp was even issued. In addition, the Peter Minuit Plaza near the Staten Island Ferry Terminal was officially dedicated, and a Dutch royal, Prince Bernhard, arrived to give a speech at St Mark’s-in-the-Bowery. Musically, the icing on the cake was provided by the Canadian male quartet The Four Lads, who brought together New Amsterdam, Istanbul (Not Constantinople), and New York City in a song that became their first gold record. New Amsterdam only gets a cameo appearance:

“Even old New York was once New Amsterdam

Why they changed it I can’t say

People just liked it better that way”

But it still raises an important question: why was New Amsterdam renamed New York? And who preferred that name?

Manahatta

The story of the city’s name has little to do with what those living there actually wanted. Before there was a city, there was an island called Mana-hatta by the Native Americans. There are various etymologies of the name, ranging from ”hilly island” to “the place where we all got drunk.” The association with alcohol has its origin in the spirits provided by Europeans, which—like infectious diseases, devastating warfare, and land grabbing—was extremely harmful to the Native Americans. The name “Manahatta” featured on a Dutch map as early as 1614, but doubtlessly had been used by the Native Americans for a long time. The Dutch explorers and traders also applied the name to the island’s inhabitants, calling them the “Manatthans.” In this case, the newcomers adopted a Native American name, but they often used names of their own for the geographic features they encountered (like Staten Island, Arthur Kill, Hellgate, Long Island, all Dutch names in origin, but subsequently anglicized). This speaks to what was going on in the seventeenth century: two distant European countries, the Dutch Republic and England, engaged in a rivalry that shaped the history as well the names of New Amsterdam/New York.

After initial forays in the sixteenth century, the Dutch were the first Europeans to explore the waterways around Manhattan and set up trading relations with the Native Americans. The English had already established a small settlement in Virginia and invoked a royal English charter to claim the area where the Dutch conducted their activities. Diplomatic confrontations in Europe were the main impulse behind the Dutch establishing a permanent presence there. This included a small colony on what is now called Governors Island. Within a short time, the focus of the Dutch colonization effort became fixed across the water on the southern tip of Manhattan, where the Dutch West India Company (WIC) established a fort. The branch of the WIC in charge of this minor settlement was based in Amsterdam and, thus, the fort was called Fort Amsterdam. There was nothing unique about the name, as the Dutch established any number of forts and settlements named after Amsterdam in the Caribbean, South America, Africa, and in Asia.

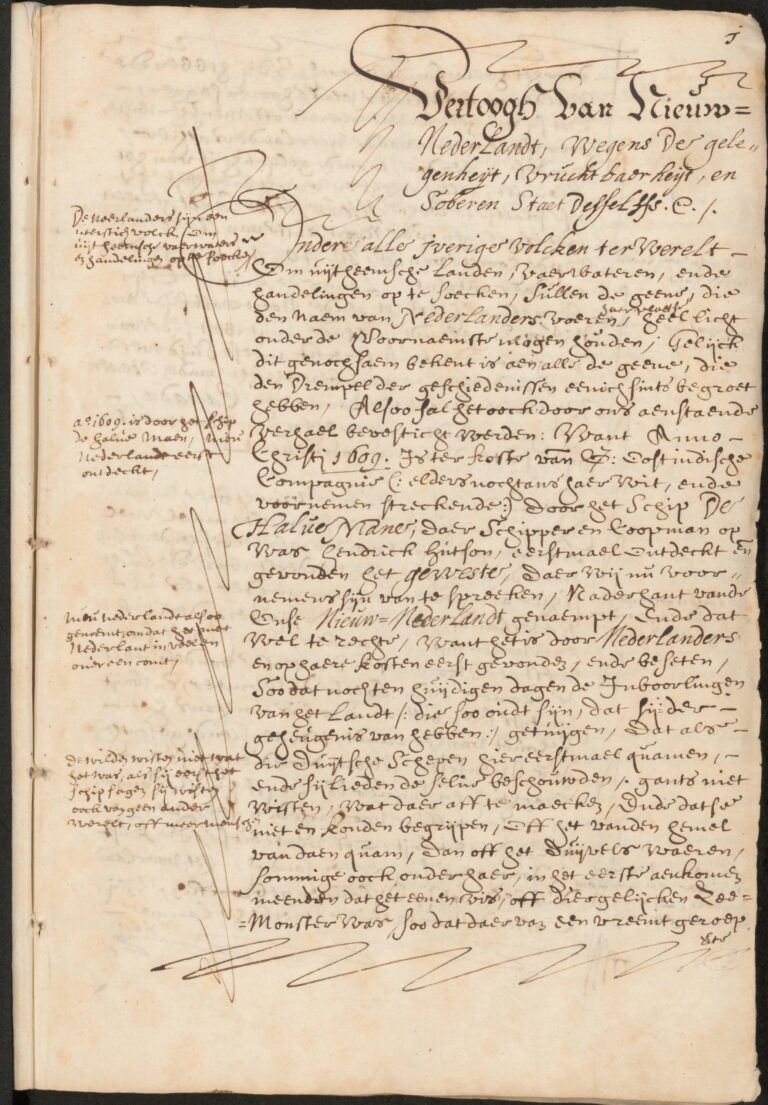

Fort Amsterdam

Unlike most fortifications named after Amsterdam, Fort Amsterdam on Manhattan developed into a civil and administrative center of some importance. Thus, many of the documents drawn up in the offices in the fort were dated and signed at “Fort Amsterdam in New Netherland.” But the existence of a mere fort was not enough. In order to boost its claim, the West India Company also dispatched a group of Walloon settlers to provide “boots on the ground.” Quickly, a small village sprang up around the fort. The village developed into a small town, which in 1653 acquired its own court of justice and city rights. And the magistrates of the city signed their official documents in their Stadthuys or City Hall at “Amsterdam in New Netherland.” The appellation “New Amsterdam” was only occasionally used, however, mostly in informal writings as shorthand for the longer name. Of course, both components of the name were equally significant in the view of the New Amsterdammers. ‘Old’ Amsterdam in Europe had not just supplied the name, it served as a model and was explicitly emulated in economic, administrative, legal, and religious matters. And yet, the city was ‘new’, in the same way that New Netherland was new. According to Adriaen van der Donck, who published an extensive description of the colony with the aim of boosting the colonization effort, New Netherland was fertile and situated in a moderate climate, possessing good opportunities for trade, harbors, waters, fisheries, weather, and wind and many other worthy appurtenances corresponding with the Netherlands, or in truth and more accurately exceeding the same. So it is for good reasons named New Netherland, being as much as to say, another or a newfound Netherland.

That is pretty much what all European colonizers did, from New Spain and New France to Newfoundland. They divided up the “New World” and named it after their European homelands. This included of course England and New England. The English still did not acknowledge the Dutch claim to New Netherland, however, nor did the colonists in New England, who cast envious eyes westward, to the fertile soil of Long Island and the flood plains along the North River, which they preferred to call “Hudson’s River.” Rivalry between the English and the Dutch continued on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean and ultimately erupted into war in 1652. This furnished some of the New England colonies, in particular New Haven and Connecticut, with an opportunity they jumped at with an eagerness bordering on aggression. Two New England emissaries obtained permission as well as ships from the English government to launch an attack on New Amsterdam. Thus armed with both the authority and the military power that had been lacking previously, they sailed for Boston. The news of their arrival quickly made it to New Amsterdam, where the authorities hastily started to repair the fort and build a perimeter defense, consisting of “an upright stockade and a small breastwork,” at the north edge of the town. The resulting ditch and fence were later dubbed “Wall Street.” But its worth was never put to the test. Just before the English ships were due to set sail from Boston, news arrived of a peace settlement in Europe. New Amsterdam had been saved by the bell. at least for now.

A Royal Gift

Some of the New England colonies were disappointed by this turn of events, but they did not shelve their ambitions. Encroachments into New Netherland continued but were mostly thwarted by the Dutch colonial authorities. Meanwhile, George Downing, the English ambassador in The Hague, continued his diplomatic attacks on the West India Company, arguing that he knew of no country by the name of New Netherland, except on the map. By 1660, the chances of the New England colonists were boosted when Charles II finally ascended to the throne and the monarchy was restored. Despite having enjoyed the hospitality of the Dutch during his years in exile, he was receptive to proposals from New England for a renewed attempt on the Dutch colony. In early 1664, with tensions between the two countries at their height, the king granted a large swathe of North America to his brother, the Duke of York. A small fleet was quickly assembled and sailed across the Atlantic. After stopping at Boston to alert the militias of the New England colonies, the combined land and sea forces advanced on New Amsterdam. This time, nothing could save the city, as the attack took place in peacetime. Soon, Richard Nicolls was master of “Fort James in New Yorke upon the Isle of Manhatans.” The regime had changed and so had the place-names.

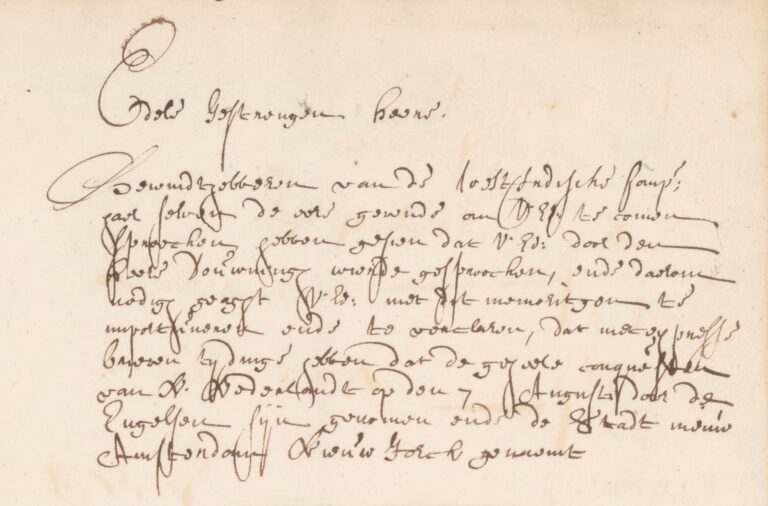

The news of the fall and renaming of New Amsterdam reached Amsterdam several weeks later. A few directors of the West India Company immediately travelled to The Hague to communicate the news to Johan de Witt, the Grand Pensionary of the Dutch Republic. When they met De Witt, he was in conversation with none other than the English ambassador, George Downing. The directors of the WIC handed De Witt a hastily scribbled note, to avoid alerting Downing to the news.

Another War, Another Peace

Inevitably, a military attack in peacetime led to war. In the Second Anglo-Dutch War, the Dutch fared better than the English, who, leaving aside the Fire of London, suffered an ignominious defeat when the Dutch fleet sailed up the Medway River, raided the English naval base at Chatham, and returned triumphantly with the flagship Royal Charles in tow. Both sides were now eager for peace, which was swiftly concluded at Breda. To speed up the proceedings, the Dutch and English agreed to apply the principle, which meant each country would keep what it controlled when the war ended. Thus, England kept New York and the Dutch Republic retained Surinam. Other colonies were involved as well, so this was not a simple one-to-one swap, as it is sometimes presented.

The Peace of Breda left the Chatham insult to royal pride unavenged and Anglo-Dutch competition unresolved. It is hardly surprising then that a new war broke out only a few years later. This time, the Dutch Republic barely survived the combined onslaught of English and French forces. Yet two of its fleets joined forces and unexpectedly sailed into the New York Bay. The English were slow to surrender, upon which the Dutch commanders unleashed a force of six hundred “sea soldiers”, i.e. Dutch marines, who took the city in an amphibious assault. Again, the place-names changed: New York became New Orange and Fort Willem Hendrick replaced Fort James. Both redesignations referred to the new stadtholder of the Dutch Republic, Hendrick Willem of Orange. But Dutch control did not last long. Another peace treaty was agreed upon and this time the possessions each country had held before the war were required to be returned. New Orange thus became New York again. The Dutch inhabitants grumbled, but the English, especially the Duke of York, liked it better that way.

So that is why old New York was once New Amsterdam and why the name was changed. It is not remarkable that one name replaced another several times. After all, there are many instances in history of this type of thing happening when a regime change occurs. In the case of New York it is unusual that the name remained unchanged subsequently, despite a regime change. After British troops left the city in 1783, at the end of the Revolutionary War, it would have made perfect sense to get rid of a name so closely connected to the British monarchy. But the Americans, now independent in their new nation, didn’t change the name. They liked it fine as it was.

Jaap Jacobs (PhD Leiden, 1999) is affiliated with the University of St Andrews. He is a historian of early American history, specifically on Dutch New York. He has taught at several universities in the Netherland, the United States and the United Kingdom.

This blog is the third of a monthly series with stories from the rich history shared by the American and the Dutch people. Authors from both countries will present various stories of their own choosing, from a wide variety of perspectives, in order to provide the full picture of the triumphs and heartbreaks, delights and disappointments that took place throughout hundreds of years of shared history. Not all stories will be ‘feel-good history’, however. While the relations between the Dutch and the Americans have for the most part been stable and peaceful, their shared history contains some darker moments as well. Acknowledging that errors have been made in the past does not take away from the friendship but, rather, deepens it.

This story was first published on the 19th of June 2022 on the website of the Dutch National Archives.

About the author

Jaap Jacobs (PhD Leiden, 1999) is affiliated with the University of St Andrews. He is a historian of early American history, specifically on Dutch New York. He has taught at several universities in the Netherland, the United States and the United Kingdom.

About the blog series

This blog is the third of a monthly series with stories from the rich history shared by the American and the Dutch people. Authors from both countries will present various stories of their own choosing, from a wide variety of perspectives, in order to provide the full picture of the triumphs and heartbreaks, delights and disappointments that took place throughout hundreds of years of shared history. Not all stories will be ‘feel-good history’, however. While the relations between the Dutch and the Americans have for the most part been stable and peaceful, their shared history contains some darker moments as well. Acknowledging that errors have been made in the past does not take away from the friendship but, rather, deepens it.

Further reading

Donck, Adriaen van der, A Description of New Netherland. Ed. Ch.T. Gehring, W.A. Starna, trans. D.W. Goedhuys (Lincoln: (Nebraska University Press, 2008).

Jacobs, Jaap, Competing Claims: International Law, Diplomacy, and Anglo-Dutch Rivalry in 17th Century North America, David Ormrod & Gijs Rommelse (eds.), War, Trade and the State: Anglo-Dutch Conflict, 1652-89 (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2020), 203-229.

Jacobs, Jaap, Dutch Colonial Fortifications in North America 1614-1676 (e-book, Amsterdam: New Holland Foundation, 2015).

Roper, L.H., The Fall of New Netherland and Seventeenth-Century Anglo-American Imperial Formation, 1564-1656, The New England Quarterly, vol. 87, no. 4, 666-708.

Sources

Dutch National Archives, collection 4.VEL, foreign maps, inv. nr. 520.

Dutch National Archives, collection 4.VELH, foreign maps supplement, inv. nr. 619.14.

Dutch National Archives, collection 1.01.02, Staten Generaal, loketkas, inv. nr. 12564.30A.

Dutch National Archives, collection 3.01.17, Johan de Witt, inv. nr. 1008.

To sponsor a post, contact us at

info@newamsterdamhistorycenter.org