The Story of Manuel de Gerrit de Reus

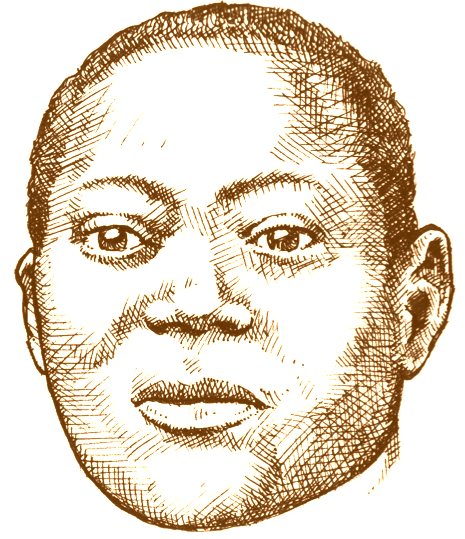

On a cold day in January of 1641, Manuel de Gerrit de Reus climbed the ladder that would be his place of execution. Before him stood New Amsterdam’s population, ready to bear witness to the court’s ruling. Behind him stood the West India Company’s executioner, another enslaved African, who secured not one but two ropes around Manuel’s neck to compensate for his great size and weight. To carry out the sentence of death as punishment for murder, the executioner pushed Manuel from the ladder. But this was not the end of Manuel’s life story, which tells us much about slavery in Manhattan’s early days.

Manuel de Gerrit de Reus was among the first enslaved people brought to New Amsterdam by the Dutch West India Company in 1626, probably captured from a Spanish or Portuguese vessel by Company privateers. In desperate need of workers, Company officials turned to slave labor to build the fort, cut timber and firewood, clear land, burn lime, and harvest grain. Since much of this work was seasonal, enslaved people were sometimes rented to other residents. It is believed that Manuel was rented for a long period of time to Gerrit Teussen de Reus, one of Manhattan’s original farmers, whose name helped distinguish Manuel from other enslaved Africans with the same name. Manuel’s great physical stature also earned him the nickname “Giant Manuel.’”

Manuel de Gerrit de Reus was among the first enslaved people brought to New Amsterdam by the Dutch West India Company in 1626, probably captured from a Spanish or Portuguese vessel by Company privateers. In desperate need of workers, Company officials turned to slave labor to build the fort, cut timber and firewood, clear land, burn lime, and harvest grain. Since much of this work was seasonal, enslaved people were sometimes rented to other residents. It is believed that Manuel was rented for a long period of time to Gerrit Teussen de Reus, one of Manhattan’s original farmers, whose name helped distinguish Manuel from other enslaved Africans with the same name. Manuel’s great physical stature also earned him the nickname “Giant Manuel.’”

Like many other slaves, Manuel held certain rights in New Amsterdam. He could marry, own moveable property, and he could raise his own crops and animals for personal use and for sale. He participated in New Amsterdam’s legal system by petitioning the government, testifying in court against a white man, and granting a power of attorney to the company’s commissary in Rensselaersyck to help him collect money he was owed.

In January, 1641, the company slave Jan Premero was found murdered. Nine other company slaves, including Manuel de Gerrit de Reus, confessed to the murder knowing it was a capital crime in New Amsterdam and perhaps recognizing the reluctance of the company to execute nine of its thirty slaves. Since no single individual confessed to inflicting the lethal blow, the Provincial Council (acting in a judicial capacity) ordered the drawing of lots to determine who would be punished. They believed that the hand of God would intervene to help identify the perpetrator. Manuel drew the short straw and was sentenced to death by hanging. But when Manuel was pushed off the ladder, both ropes broke and he fell to the ground. The crowd shouted for mercy, convinced that a failed execution was an act of God. The Provincial Council agreed and pardoned all nine slaves on condition of good behavior and willing service.

Three years later, in 1644, Manuel and his cohort, now joined by two more enslaved Africans, petitioned the Director and Council for their freedom claiming it was deserved after many years of service and that it was impossible to support their wives and children in the company’s service. Although they were not the first to request their freedom from the Company, the Eleven’s petition came at a critical moment for the colony – during Kieft’s War against the natives. It is likely that Manuel and the remaining petitioners had helped in the colony’s defense, armed by Director Willem Kieft with pikes and hatchets, and hoped to be rewarded for services rendered. The Company granted their request, but with restrictions. Manuel, the others, and their wives were granted their freedom but were required to pay an annual quitrent to the company of 30 schepels of wheat and one fat pig. They were also required to serve the Company, with pay, whenever required, and they agreed that their children would remain enslaved to the Company. Within a year, the Eleven were granted plots of land for farming and housing, outside of the city wall and north of the Fresh Water Pond. In the next twenty years, they would be joined by almost twenty other former slaves creating the first racially segregated but free Black community in Manhattan.

With four English naval vessels sitting in the bay, awaiting New Amsterdam’s surrender in September 1664, nine “half free” slaves petitioned the Company to be “made entirely free.” Their request was immediately granted. Manuel de Gerrit de Reus was not among them, though he still held title to his land near what is today’s Washington Square Park. His free status and land ownership were soon confirmed by the new English government.

At the time of the surrender, Manuel was one of 75 freed slaves living on Manhattan. But there were an additional 300 Africans that remained enslaved, many of whom had recently arrived aboard the Company ship Gideon. Unlike Manuel, their future was uncertain, as was the future of those Manhattan residents who remained enslaved. The institution of slavery that had once shown signs of flexibility would gradually begin to tighten.

We hope you’ve enjoyed our articles and information. If you would like to contribute to help us promote and spread the history of the early New York, please click and discover more about our programs, what we offer and ways you can help.

To be a sponsor email us at: events@newamsterdamhistorycenter.org