Breaking Free from a Girls’ Boarding School?

American Mass Culture and the Roaring Twenties in theNetherlands #18

Written by Kees Wouters

During the 1920s, the Netherlands excelled in dullness, it is said. But Kees Wouters shows how the cobwebs of pillarized society were blown away by a new musical wind from the West: Jazz! Exalted by many, villified by others, Dutch musicians playing American jazz conquered music halls and radiowaves alike and even made the Dutch dance.

According to Dutch historian Hermann von der Dunk, writing in the early 1980s, life in the Netherlands after World War I was as exciting as in a girls’ boarding school. Nothing much happened. Despite the presence of about a million destitute Belgian refugees, the horrors of the Great War had largely passed the Netherlands by. After an initial push for renewal from a few pacifist and Christian groups, the thoroughly pillarized society remained unshaken, ensuring a “ban on mixed bathing, a strict film censorship and a pillarized broadcasting system.” The Netherlands had no fatherless families and no traumatized soldiers, it did not undergo the “leveling effect of war, which elsewhere wiped out ranks and classes,” but remained an “unshaken class society,” well-behaved, conservative, and God-fearing. In his assessment, Von der Dunk referred to a cultural elite which displayed a distinct anti-confessionalism, but its rebellious undertone limited the influence of writers, poets, and artists. It condemned them to a marginal position, “almost resulting in the creation of an intellectual pillar of their own.”

Well-behaved?

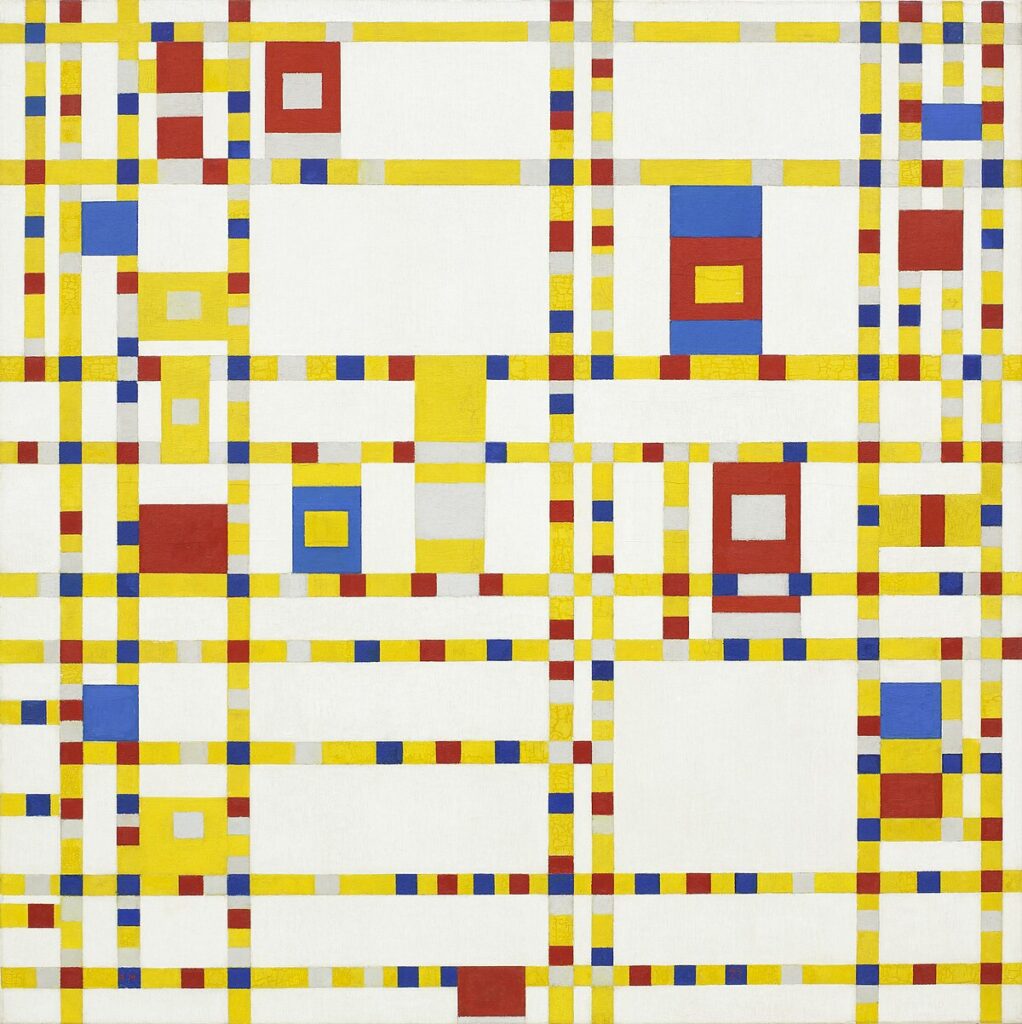

That is quite a sweeping statement, but it has not remained unchallenged. Recent historical research shows that the new generation of Dutch artists and writers were anything but isolated. “The Netherlands was no girls’ boarding school and was not in a lull,” acclaimed Dutch historian Frits Boterman recently posited. The main source of inspiration for Dutch artists and intellectuals was Germany, not America. Modernists such as Piet Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg, Bart van der Leck, and Gerrit Rietveld moved away from realism and German-style expressionism and, forming their movement De Stijl, they provided the backbone of an abstract cultural avant-garde, which reached only a small cultural elite. The same applies to cultural critics such as historian Johan Huizinga, writer Menno ter Braak, and poet Hendrik Marsman. They were encumbered by the sombre cultural pessimism of the German philosopher Oswald Spengler, who in his book Der Untergang des Abendlandes argued that every idea of progress was an idée fixe. In his view, Western culture was just a “dying civilization.” This leaden gloom burdened but a few. The general public instead took on modernity, optimism, and a carefree attitude from an entirely different direction: America. New media, such as the cinema, the gramophone, and, a few years later, the radio, opened wide the windows and doors of the girls’ boarding school.

Movie Palace

The cinema grew into a truly popular form of entertainment in the 1920s, with a dominant role for still silent but very romantic Hollywood films. In 1921, Abraham Tuschinski opened his famous cinema theater in Amsterdam. It was a movie palace full of glamour and luxury, in which violinist Max Tak created a furor with his Tuschinski theatre orchestra. Tak added a sousaphone, saxophones, and a brass section to the strings of his orchestra and alternated the usual entertainment repertoire with swinging tunes like “I Can’t Give you Anything But Love,” “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” and “Ain’t She Sweet.”

As early as 1919, the first American dance records appeared on the Dutch market. The same year, many dance schools introduced ‘Jes’, ‘jas’ or ‘yasz’ (the exact spelling was as yet unknown) as a new American dance. In 1920 the English five-man orchestra The London Five performed in The Hague and the same year Amsterdam dance teacher James Meyer founded the first Dutch professional jazz orchestra: the James Meyer’s Jazzband, led by pianist Leo de la Fuente.

Come 1921 and the post-war dance frenzy erupted in full force. Out went the Wiener Damenkapelle, the salon orchestras and the melodies of Johann Strauss and Franz Léhar; people wanted jazz instead. The music halls introduced one fashionable American dance after another: the “Shimmy,” the “Charleston,” the “Black Bottom.” A huge replica of the Statue of Liberty appeared on the stage of the Rotterdam dancehall Pschorr with the text “Welcome to New York” over it. A big drum, equipped with a horn and an enamel pan, joined the strings to make the ensemble a jazz orchestra. Very soon more was needed. To make up for the lack of brass, jazz bands recruited trumpeters, saxophonists and clarinetists from military bands. Older musicians, such as string players and pianists, took up wind instruments instead.

American Examples

The post-war generation of Dutch musicians followed the American example and formed jazz bands of their own. In 1924 Theo Abels launched The Original Victoria Band, and two years later Jack and Louis de Vries, Theo Uden Masman, and Kees Kranenburg founded The Ramblers. The Willebrandts brothers started their orchestra in 1929. Jazz orchestras featured on the radio for the first time in 1923, but they did not reach a large audience until the late 1920s. Dutch concert practice also initially remained devoid of American musicians. Jazz stars like Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Freddy Johnson and Coleman Hawkins, visited the Netherlands from the 1930s onwards. The only exception was Paul Whiteman, who performed with his orchestra in the Netherlands as early as the summer of 1926. The three concerts, two at the Kurhaus in Scheveningen and one at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, were completely sold out and elicited jubilant reactions. “Here the spirit of jazz enters into an entente-spiritual with that of the old world,” according to De Maasbode. “Unmistakably stunning,” said the Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant, “A precious and colorful polytonal film-in-sounds.” Het Vaderland invoked Willem Mengelberg, the famous director of the Concertgebouw Orchestra, and called Whiteman’s orchestra a “Mengelbergsch ensemble, a splendid organism, in which every link works perfectly. In the full strength of this ensemble is a dash of brutality, a dash of humor, a dash of tiger-shining beauty.”

Decency under Threat

However, this infectious enthusiasm met with a swell of criticism by dour Dutch killjoys. The steadily increasing popularity of American music and the new dances set off alarm bells among the guardians of the boarding school. A storm of moral indignation arose from all corners of the pillarized Dutch society. In a report on modern dancings, De Maasbode on January 7th, 1927, noted with dismay that the dancing couples were performing all kinds of movements, “the origin of which lies with barbarian Negro tribes that excite themselves to erotic madness and in which brutal primal instincts of both sexes try to celebrate themselves.”

Increasingly, jazz music and modern dances became associated in the press with barbarism, primitive instincts, and eroticism. Hospitality operators responded to the negative image by imposing strict requirements on the appearance and demeanour of the musicians. Professionals as well as amateurs had to behave properly during a concert. Clothing, hairstyle, presentation, everything had to be impeccable in order to make a respectable and civilized impression. After all, critics of all persuasions were on the lookout, and the owners of the dance establishments were very careful to ensure that with the arrival of the new music, at least the semblance of good manners and decency was maintained. No excessive drinking or dance music, because at the slightest whiff of impropriety the police were ready to revoke the tap or music license.

Especially the Catholics attempted to protect the girls’ boarding school from the superficial and immoral American mass culture. In 1928, the priests of the city of Utrecht joined forced to warn against “the frivolous, yes, passionate dance music that aimed to bring the dancers into a stupor of sensuality. Truly, we are not exaggerating in saying that our modern, pagan dances are an abyss of sin. Where there is dancing, there the men are intoxicated and the women find their ruin; one cannot dance on earth and once in heaven enjoy joy.” Even chairman Koos Vorrink of the socialist Workers’ Youth Movement considered modern dance ill-suited to promote a “healthy and sincere life of the senses. It invokes a sultry and impure atmosphere, which clouds the mind.”

The Charleston in particular was to suffer. According to the Vereeniging voor Eer en Deugd (Association for Honor and Virtue), the modern dance hall looked like a lunatic asylum: “No wonder that in the Netherlands the owners of dance halls, who value ‘neat’ occasions, have long since rejected the Charleston as an outgrowth of modern Negro entertainment.” At dance hall Trianon in Amsterdam and at the Centraal in The Hague, the unseemly dance had already been banned and numerous newspapers and magazines urged a national ban.

The Dutch Don’t Dance

In the end, the attempts to ward off American influences on Dutch society met with limited success. The residents of the boarding school did not allow themselves to be curbed. Apart from a few dance hall operators who, fearful of reputational damage, kept the Charleston out of the house, there was no actual government intervention on public morality in the Roaring Twenties. That changed in the Tired Thirties. On the initiative of the Disciplinary Union, an organization that had made a statutory commitment to “fight against indiscipline and to beautify public life,” a Committee on Folk Entertainment, in 1927, had asked the government to act against modern dance entertainment. The request was granted, and in 1930 a governmental committee was installed, which completed its work a year later. It produced a damning report. Modern dances posed a moral danger to the youth, it concluded: “Moral decay invaded us in all kinds of ways from the countries involved in the war. In its manifestation, however, it is essentially American.” As a result the government in 1933 introduced a ban on dancing in public places. The measure was quite ineffective, as by that time the economic crisis had already limited dancing to private occasions or special ‘club’ evenings. During the last years of World War II, the windows of the girls’ boarding school appeared to be completely sealed. They never closed again once the war was over.

About the author

Kees (C.A.T.M.) Wouters (PhD Amsterdam 1999) is an independent author and filmmaker. As an historian, he focuses on 20th century Dutch and German cultural history. He is director of various documentary films on the Second World War and the Dutch East Indies.

About the blogseries

This is the eighteenth installment in a monthly series of blogs telling stories about the rich history shared by the American and the Dutch peoples. Authors from both countries will be presenting accounts of their own choosing, from a wide variety of perspectives, in order to give as full a picture as possible of the triumphs and heartbreaks, delights and disappointments that took place over hundreds of years of shared history. Not all these stories will be ‘feel-good history’, however. While the relations between the Dutch and the Americans have for the most part been stable and peaceful, their shared history contains some darker moments as well. Acknowledging that errors have been made in the past does not take away from this friendship but, rather, deepens it.

Further Reading

Boterman, Frits, “Nederland en Duitsland in de jaren twintig,” in Rinus Nederlof et al. (ed.), Leven in een stroomversnelling, Nederland in de jaren na de eerste wereldoorlog (Doorn: Museum Huis Doorn, 2023).

Dunk, H.W. von der, “Nederlandse cultuur in de windstilte,” in Kathinka Dittrich et al., (ed.) Berlijn-Amsterdam 1920-1940: Wisselwerkingen (Amsterdam: Querido, 1982), 25-30.

Kroes, Rob, “De Verenigde Satan van Amerika: anti-Amerikanisme in Nederland,” in Maatstaf, vol. 33-2 (1985), 71-79.

Sources

“Charleston,, de laatste dansontaarding,” in: Mannenadel en vrouweneer: Orgaan van de Vereeniging “Voor Eer en Deugd,” 1 December 1926, 83,85.

“Kuhrhaus. Paul Whiteman en zijn orkest,” in Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant, 26 June 1926.

“De moderne dansen – Het oordeel van H. Borel,” in De Maasbode, dagblad voor Nederland, 7 January 1927, 1.

“De zedeloosheid der moderne dansen – Een schrijven van de gezamenlijke pastoors der stad Utrecht,” in De Maasbode, dagblad voor Nederland, 4 September 1928, 1.

Bie, H. de, and R.J.Th. van der Heyden, Rapport der Regeerings-commissie inzake het dansvraagstuk (’s-Gravenhage: Algemeene Landsdrukkerij, 1931), 11.

National Archives of the Netherlands, collection 2.22.15, collection governmental publications, inv. nr. 5310.

L.W., “Kurhaus, 8.15 u. Paul Whiteman and his Orchestra,” in Het Vaderland, Staat- en letterkundig nieuwsblad, 23 June 1926, 1.

Vorrink, Koos, “Enkele teoretiese en practiese opmerkingen over volksdans,” in Volksontwikkeling: maandblad uitgegeven door het nutsinstituut voor volksontwikkeling, July1927.