Jersey City’s Dutch Roots

by Firth Haring Fabend, Ph.D

A talk presented at the Jersey City Public Library at the unveiling of a plaque to commemorate New Jersey’s colonial roots by the Society of Colonial Wars of New Jersey, October 14, 2023

In 1833, Washington Irving and his good friend Martin Van Buren, Vice-President and soon to become the eighth President of the U.S., traveled down the Hudson River Valley from Kingston, NY, to Jersey City on what Irving labeled their “Dutch tour.”

In writing of this trip, Irving described the local farmers along the way as Dutch, even though we now know that half of them were non-Dutch of other European origins, and even though they had been in America since the founding of the colony of New Netherland in 1624. They wore, like farmers in Holland, Irving wrote, calico “pantaloons,” lived in “very neat Dutch stone houses,” drove Dutch wagons, spoke Dutch, and were married to wives who wore (unfashionable?) Dutch-style sunbonnets [1]. Irving’s impressions of Jersey City in 1833 echoed the stereotypes he had already invented in 1809 in his popular Knickerbocker’s History of New York with its amusing depictions of the Dutch-descended people in the Hudson Valley.

Not everyone had been amused. In fact, the reception to Knickerbocker’s History had been so negative among the Dutch community, which took umbrage at Irving’s lampoonish exaggerations of their ancestors and governors, that Irving, his ears still burning forty years later, felt obliged in the 1848 edition of the History to apologize for “having taken an unwarrantable liberty with our early provincial history.” [2]

That history as far as Jersey City is concerned began in 1630, 200 years before Irving’s Dutch tour, when Jersey City had its origins in a land grant to Michiel Pauw, a director in the Dutch West India Company. The list of events on the plaque unveiled today, starting from 1630 and ending in 1664, begins with that particular event. The grant to Pauw consisted of roughly eight miles of fertile land directly on and across the Hudson River from New Amsterdam on the peninsula where Indians arrived from the hinterland with their peltry. It extended west from the Hudson to the Hackensack River and north to today’s Bergen County line. It also included Staten Island. By what were three separate transactions, Pauw became a Patroon, an owner of vast tracts of land and substantial requirements for peopling it.

Pauw, who did not himself settle on this land, and there is no evidence that he ever even visited it, called the huge tract Pavonia, a Latinized version of his name, and he had great expectations for it. But his colleagues in the Company back in Amsterdam were envious that he had scored this real estate prize while they were left out. Resentments simmered, and when Pauw failed to settle his land with fifty “souls” age fifteen years and up, as his patroonship stipulated, they pounced and required him to resell the land to the Company.

The Company, to protect its investment, then hired Pauw’s on-site overseer, Cornelis van Vorst. To ensure that he remain in place to manage the property, they built Van Vorst a frame house thatched with cattails to seal the deal. [3] An enterprising and capable man, Van Vorst did just that, managing the patent lands, farming and raising cattle as well, and trading with the local Lenape Indians on the side. He died young only eight years later in 1638.

A few months after his death, Van Vorst’s widow, Vroutje Ides, signed a contract with newly arrived Director Willem Kieft to continue renting the farm where she and Cornelis had been living. She also agreed to build a new house for which Governor Kieft promised her the bricks needed to erect the chimney. [4]

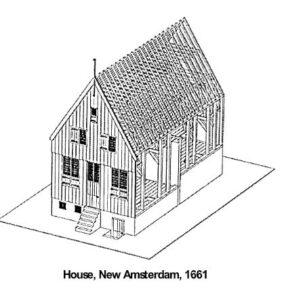

Vroutje’s contract with Director Kieft presents an opportunity to consider housing in Pavonia in that first decade. Though no physical traces remain of the early homesteads, many references to reed and thatched roofs in the printed records are evidence of the nature of the first shelters–and of many coming even quite later. However, references in the records of Kieft’s administration also describe more substantial dwellings. Six such structures are shown on the Manatus Map of 1639 along the Jersey shore representing, today, from Jersey City at the far left to Weehawken at the far right with Paulus Hook, Hoboken, and Ahasimus (or Harsimus Cove) in between.

An authority on the domestic architecture of New Netherland has found, based on nineteen surviving carpenters’ contracts and other evidence, that such substantial houses as these were actually traditional Netherlandic-style dwellings, constructed using a structural bent system with reinforcing braces, as opposed to the timber framing of English dwellings. Vroutje Ides’ new house, with the brick chimney referred to by Kieft, this authority speculates, would probably have been similar to the house pictured in this image, which was built in New Amsterdam in 1661 [5]

Vroutje’s 1639 lease also stipulated that she finance the actual building of the new house at her own expense. Again, there is evidence in the records that this widow was well equipped to do so: the 1641 inventory of her possessions when she died that year (also young) suggests how successful this frontier couple had been in their short time together. The inventory takes up a full page and a half in Charles H. Winfield’s History of the County of Hudson, NJ, and shows what he described as the “personal effects of a well-to-do family in those days.”

Vroutje’s 1639 lease also stipulated that she finance the actual building of the new house at her own expense. Again, there is evidence in the records that this widow was well equipped to do so: the 1641 inventory of her possessions when she died that year (also young) suggests how successful this frontier couple had been in their short time together. The inventory takes up a full page and a half in Charles H. Winfield’s History of the County of Hudson, NJ, and shows what he described as the “personal effects of a well-to-do family in those days.”

Besides cash and wampum, Vroutje’s possessions included a gold ring, a silver goblet and silver spoons and cups, much clothing, including a stylish damask furred jacket, and 23 animals ranging from a pair of oxen to lambs.[6]

Despite that no physical evidence of the housing stock of early Pavonia remains, contracts, leases, and wills and inventories from the early decades suggest that they were years of growth and even prosperity, at least for some. I think Winfield would agree that a family with the amount of material things that Vroutje left at her death would not likely have chosen to live in a sketchy dwelling roofed with cattails.

They were also years of calm, compared to what would come next: Violent Indian wars erupted in two main waves over the decades of the 1640s and mid-1650s interrupted intermittently by fragile peace treaties and unpredictable flareups of violence.

Although differences between the European settlers and the Lenape Indians had existed from the beginning, the two cultures had coexisted peaceably for the most part in the first two decades, knowing it was to their mutual advantage to do. But a slowly dawning realization was gnawing away at the Indians that the interlopers from “over the salt water,” as they described them, were there to stay, and their introduction to alcohol and guns was fateful.

The situation was exacerbated in 1639 by Director Kieft soon after his arrival when he made a disastrous decision to “exact a tribute” from the Lenape, specifically a “contribution” of maize, furs, and wampum ostensibly in return for the Company’s expenses in providing military protection for them from their Mohawk enemies. [7]

The Lenape were indignant. They did not need such protection, they insisted, and they did not want to pay for what Kieft considered the Company’s outlay on their behalf. In their minds, they were “paying” in other ways by supplying the fur pelts that undergirded the local economy and by allowing the settlers to use their land, though not to own it–although, of course, the Europeans regarded the transactions as done deals. For Indians, though, land could not be “owned,” much less be alienated from them. And so, they refused to make such a contribution, while Kieft persisted in demanding it. In 1641, the revenge killing of a defenseless settler by an Indian with a long memory of an old murder began to bring matters to a head. An alarmed Director Kieft thought it wise to form a council of twelve citizens to advise him on how to punish the Indians. The Twelve advised delay.

The pause lasted for two years, but in 1643 dissension erupted into a full-fledged war when Kieft was persuaded by three of the original Twelve councilors to attack the Indians to avenge that old murder. This has become known to history as Kieft’s War.

On the night of February 25, 1643, in Pavonia, on his order, Kieft’s men slaughtered 120 unarmed Indians and their wives and children as well as 40 Indians in a second massacre the same night on the east side of Manhattan.

The surviving Indians fled for protection to the Fort in New Amsterdam, believing the Dutch to have been innocent in these horrific attacks. But “They were soon undeceived,” Winfield writes, and the two sides “entered upon a relentless war.”

All of the farms or bouweries in Pavonia were destroyed, and the territory “from Tappan [in today’s Rockland County] to the Highlands of the Navesink [River] returned to the sole possession” of the Indians. Six months later, at the end of August, acknowledging their inescapable mutual agricultural needs, the two sides entered into a treaty of peace, and the settlers cautiously returned to Pavonia to rebuild their houses and replant their desolated fields.

Much displeased in Amsterdam by Kieft’s judgment, the Dutch West India Company recalled him in 1646 in spite of the new treaty and appointed Petrus Stuyvesant Director General. Kieft was drowned in a shipwreck on the way back to the Netherlands.

Now the long Stuyvesant era of seventeen years began, an era that had its benefits not only for New Amsterdam, but for its little sister Pavonia across the river. The plaque does not mention Stuyvesant’s arrival in 1647, but history records that he was at first likened by the people to a peacock for his proud, preening manner (ironically so, in that peacock is the translation of the word pavonia in Dutch). A statue of Stuyvesant stood for many years in front of the Martin Luther King, Jr., School in Bergen Square, which is the oldest continuously occupied school site in New Jersey. It has recently been moved to a nearby park. The first school on the site was a log building.

Stuyvesant’s actions at reforming the badly run town soon established him, however, not only as a Company man through and through, but also a more competent one than any of his predecessors. At the direction of his superiors in Amsterdam, who were eager to reattract settlers to the colony, he purchased (and repurchased in some cases) much land for the Company, confirmed older patents that in some cases were irregular, and in general caused both New Amsterdam and struggling Pavonia across the river to flourish. During Stuyvesant’s administration of seventeen years Pavonia was enlarged beyond Pauw’s original patent to include all of today’s Hudson County with the exception of Harrison, Kearney, and East Newark.

The Indians, however, continued to be dissatisfied with the terms of the treaty that had ended Kieft’s War, complaining that promises made had not been kept, and Stuyvesant, always strategic in his thinking, conciliated them. Another war was not worth it in his estimation, and peace was reaffirmed. “Health and prosperity were everywhere visible,” as Winfield put it. Further references to this work are in the text (HCH, p. 50.) Twelve new patents were issued in 1654 alone.

Things were going so smoothly that Stuyvesant felt secure in leaving the area in July 1655 to subdue the Swedes in their settlement on the Delaware River that they called New Sweden. With a squadron of seven vessels and up to 700 men, he sailed south. But soon after he arrived at his destination, an Indian, in an orchard on lower Manhattan, picked a peach. It was not the first time that Indians had coveted this attractive fruit, which was new to them. The Dutch had come with peach trees to plant, and the juicy fruit when it ripened proved irresistible to the Lenape.

The irate owner planned his revenge. Hiding among the trees, in the dark of night, he fired upon an intruder and killed the thief, who happened to be an Indian girl. What followed demonstrates the profound sense of unfairness that had been eating away at the Indians for years. In lower Manhattan, in a reaction that seems to have been altogether disproportionate to the crime, they retaliated, 500 strong in 64 canoes. The settlers struck back in defense. The Indians fled in their canoes across the river, and “in a twinkle of an eye,” Winfield writes, Pavonia was on fire.

The attack raged for three days. (HCH, pp. 54, 55.) Twenty-eight farmsteads were destroyed, and many settlers slain, their ripening crops burnt, and their terrified cattle scattered. For the second time in ten years, Pavonia was desolated. This has been known ever since as the Peach Tree War, although historians believe that the causes were more complicated than the theft of a peach, including that Stuyvesant had attacked the Lenapes’ Swedish trading partners in New Sweden virtually at the same time.

The surviving people fled for protection to New Amsterdam again, and this time there they remained for five years. For their good, and their safety, Stuyvesant issued an ordinance in January 1656 commanding them “to form villages of compact dwellings for their protection, maintenance, and defense, and to cover no houses with straw or reed, or any more chimneys of clapboard or wood.” These sensible terms the Pavonians resisted, stubbornly preferring to remain in exile on Manhattan rather than to give up their traditional Netherlands model of living in isolated farms. Thus, the fields of Pavonia remained bleak and barren.

Determined to have his way, Stuyvesant negotiated a new peace with the Indians in 1658, repurchasing from them most of what is today Hudson County. With their metes and boundaries more secure, the people began to respond to the call of the fields from across the water, and finally the history of early Jersey City took a turn for the better. Stuyvesant got his way in the end, with the settlers agreeing to his terms and returning to Pavonia, while new settlers began to arrive from Europe.

In record time, by 1660, lots were laid out. Free to all who wanted to build on them, and exempt from taxes for six years, the people “flocked” to them, as Winfield put it. The layout of the lots was made by Jacques Cortelyou, the same surveyor who had drawn the Castello Plan of New Amsterdam that same year.

The plaque describes the town, which they called Bergen, and which was laid out where the Bergen Square section of Jersey City is today, as “New Jersey’s first chartered European settlement including first church, court, school, and ferry to New Amsterdam.”

The church was the Reformed Protestant Dutch Church, where the people worshipped at first in a log cabin, then in a small stone structure, which was replaced in 1680 by a building in the octagonal style familiar in the Netherlands. The government or “court” was also patterned on a Netherlands model and consisted of an inferior court of justice with a schout (sheriff) and three schepens (magistrates) presiding. This court dealt with offenses considered minor, such as brawls, slanders, threats, and drawing of knives or swords. More serious crimes, such as wounding, shedding of blood, whoring, adultery, robberies, smuggling, and blasphemy had to be heard in New Amsterdam by a higher court. (Winfield, HCH, Pp. 74, 78, 79.)

The village was palisaded, for as Winfield wrote, the “savage yet prowled hereabouts” (p. 90). A well was dug in the town center, so that the residents did not have to venture beyond the palisaded lots for water, and troughs were provided for cattle as well, for the same reason. A school was organized and a schoolmaster licensed.

Not everything went smoothly. Absentee owners, living in New Amsterdam and holding the lots for investment purposes, were a problem, for their absence meant more work for those who lived where they owned and bore the burden of community service and protection. The remedy was at hand. The ever-vigilant Stuyvesant foiled this trend with an ordinance in 1663 requiring everyone who owned a lot to live on it and do their part in protecting it from Indian attack, or to supply a substitute to share the communal burden. The remedy worked.

Not everything was perfect, of course, but everything was looking up, for Pavonia, for New Amsterdam, and for New Netherland in general.

But, abruptly, the Plaque concludes: “1664, English Conquered New Netherland.”

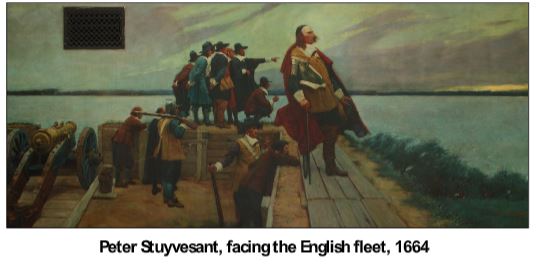

This image of Stuyvesant, alone on the ramparts, staring out at the English fleet, reminds us that he was quite alone in his wish not to surrender to the English. The people of New Amsterdam were justly afraid of the looting and plundering by the English on Long Island that they feared would result if he resisted. Even his two sons urged him to give up.

It was not only an abrupt conquering, it was an illegal one as well, because England and the Netherlands were not at that time at war. It was rather a geopolitical takeover with demographics as its inevitable provocation. Despite its robust size on the Dutch maps of the period, New Netherland was small compared to the English colonies that surrounded it north and south. And it was inconveniently positioned for England’s imperial purposes between those colonies to the north, Plymouth colony, Massachusetts Bay Colony, Connecticut Colony, and more, and Virginia colony to the south. But more important, the English colonies combined had 50,000 in population, compared to New Netherland’s puny seven to eight thousand. Basically, there was no contest. Thus it was that the colony of New Netherland came to a sudden end.

In conclusion, for lack of an earlier view, I present what is available, this artist’s drawing, dated c. 1860, of Communipaw, a village in Pavonia on the Hudson shore, today known as Upper New York Bay. This small village was formed in 1660, soon after Bergen, when it looked much as Washington Irving and Martin Van Buren might have seen it in 1833. Communipaw, in its propitious waterfront setting, was the site of the first ferry to New Amsterdam; it was connected to Bergen a couple of miles away by a wagon road that was probably an ancient Lenape trail. It is the very root, vine, and fig tree of Jersey City.

The takeover of 1664 was not the end of the Dutch legacy. The Dutch left a long-lasting impression on New York and New Jersey, and indeed on America. Although the “Dutch” houses in Jersey City that Washington Irving and Martin Van Buren observed in 1833 may have disappeared, along with much else of material culture over the centuries, the Dutch legacy survives—in our language, foods, place names, domestic and church architecture, in our melting-pot ethnic diversity, and even in our foundational documents. But that’s a story for another day.

END NOTES

1. Washington Irving, The Journals of Washington Irving. III: Spain, Tour Through the West, Esopus and Dutch Tour, pp. 187-196.

2. Washington Irving, Knickerbocker’s History of New York, 1848 edition, “Apology,” p. 548.

3. Charles H. Winfield, History of the County of Hudson, NJ, 1874; hereafter HCH.

4. A. J. F. Van Laer, NYHM: Dutch, Vol.1, Register of the Provincial Secretary, 1638-1642, pp. 124-125.

5. Personal communication, Jeroen van den Hurk, August 16, 2023. See Jeroen van den Hurk, “Building a House in New Netherland,” From De Halve Maen to KLM: 400 Years of Dutch-American Exchange, ed. Margriet Lacy, Charles Gehring, Jeanneke Oosterhoff (Munster, 2008), pp. 25-40.

6. Winfield, HCH, ch. 13, pp. 427-428.

7. Jaap Jacobs, New Netherland: A Dutch Colony in Seventeenth-Century America (Brill, 2005), pp. 132ff.