One Dutch Family’s Experience of the English, or Historians Are Never Done with History

by Firth Haring Fabend

We are all familiar with the great landowners of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Hudson Valley: Kiliaen van Rensselaer with his one million-plus acres around Albany, Robert Livingston with his 160,000 acres a little to the south, the Van Cortlandts with land stretching from the Croton River to the Connecticut boundary, and Frederick Philipse with his vast holdings in Westchester County across the Hudson River from today’s Rockland County.

My Haring ancestors were not in this category. They were one of nine middling farm families in the lower Hudson Valley who, in 1680, pooled their resources to negotiate for a tract of land from the Tappan Indians, a Lenape tribe.

These nine families, most of Dutch origin, had already been living in New Amsterdam for two generations. One of their motives in acquiring this land was to become independent of the English, who had taken over the colony of New Netherland in 1664, renaming it New York.

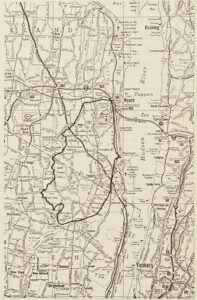

Acquiring land was a long and complicated process. When the government finally approved this transaction, it became known as the Tappan Patent (a term for deed). Today, this area would extend from West Nyack in Rockland County to Harrington Park in Bergen County—an area of 16,000 acres, roughly the size of Manhattan. Ten miles long and two to five miles wide, it was shaped somewhat like an eggplant.

Jan Pieterszen Haring bought three shares. His friend Gerrit Blauvelt purchased two shares, Adriaen Smith bought three, and three free Black families—Jan de Vries Sr., Jan de Vries Jr., and Claus Manuel—bought three shares collectively. The remaining five of the sixteen shares were purchased by families already settled in today’s Jersey City area.

Although Tappan may have been one of the few communities in colonial America where Black and white families shared equally in land ownership, it is also true, as I wrote in A Dutch Family in the Middle Colonies, 1660–1800, that early New York, like New Jersey, “was economically layered and socially stratified. Its most affluent inhabitants prospered on the labor of their slaves.”

We can imagine the patentees’ joy at having this venture approved by the government in 1683. But, alas, before they could settle on the land, disaster struck. Haring, Blauvelt, and Smith all died of unknown causes in a single month that year. At this setback, the five New Jersey families backed out of the venture, opting to hold their shares in abeyance for better times.

These unforeseen events left a core of young people—many barely out of their teens—alongside only two or three mature couples, including Haring’s widow (remarried) and the De Vries and Manuel families, to undertake what must have seemed, without their departed elders, like an impossible venture into the primaeval forest across the Hudson River.

Yet they pressed on with optimism and determination. As I wrote in my novel Land So Fair:

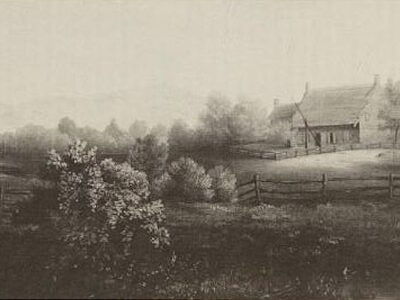

“With visions of a Paradise of milk and honey dancing in their heads, the settlers eagerly anticipated clearing the Tappan land. But this was easier said than done. The land was covered with massive hardwood trees unlike anything they remembered from the Netherlands. Felling these behemoths, cutting them into 12-foot logs, and setting aside enough for shelters, fences, and winter fuel was grueling work. Then, before the land could be plowed, underbrush had to be removed—particularly scrub oak, which was notoriously difficult due to its deep, stubborn roots. Cleared fields could revert to bush in a single year and grow into a forest within twenty. It was definitely not Paradise.”

If the patentees had hoped that moving to the Tappan Patent would shield them from English aggression, they were mistaken. In fact, their relocation may have heightened English determination to suppress them.

Yet, by the second generation after settling, the patentees had persevered. They built sturdy stone houses (some of which still stand in Bergen and Rockland counties), barns, and all the outbuildings required by busy farms. Just as they began to prosper, however, a major legal obstacle arose—again, instigated by the English.

From Land So Fair:

“The English takeover of New Netherland in 1664 was bad enough, but forty years later, two Englishmen with friends in high places sought another takeover. Quietly, they acquired property adjoining the Patent and laid claim to a strip of lush meadowland seven miles long and a mile deep along the Hackensack River. ‘How was this possible?’ the settlers cried. Their Patent described their western boundary as a ‘line running south to north to a place called the Greenbush.’ However, it did not specify ‘as the river runs.’ This omission exposed the Patent to attack under English law, which now ruled the land. Bitter controversies, debates, and demands followed over these seven square miles of meadowland. After nine years, the court ruled in the patentees’ favor. Yet it was a Pyrrhic victory, as they were forced to pay the two Englishmen a sum exceeding the original cost of the land.”

Peace, as the settlers noted, was rare. This was partly due to the precarious demographics of New Netherland. To the north and south were English colonies with a combined population of 50,000, while little New Netherland nestled in the middle with only 7,000–8,000 residents. In hindsight, it was no contest from the start.

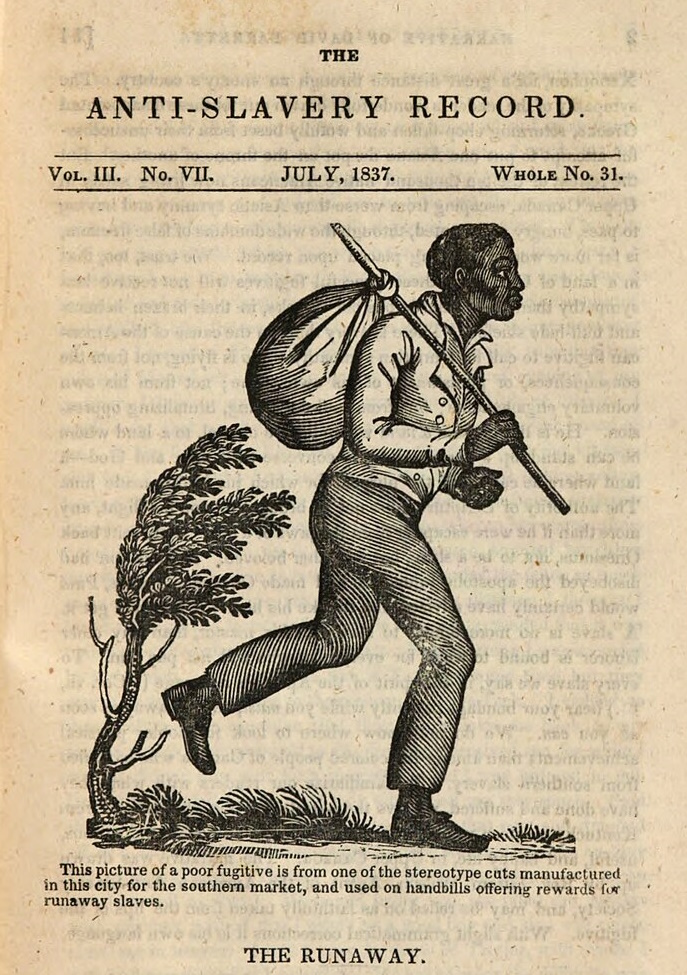

The other major obstacle was even more pernicious: slavery. The patentees’ agricultural dreams depended on enslaved labor, and the enslaved people knew it.

From Land So Fair:

“By the second generation, the once-docile Africans had begun resisting their bondage. They stole, incited riots, ran away, and occasionally killed their masters. The less adventurous slowed their work to a crawl as an act of defiance. She shivered. She had known Caesar since his birth. Would she witness his death? No, she told herself firmly. They would not hang him. But someday, she knew, he would not be there when called.”

As the Dutch in New Netherland were never done with the English, historians are never done with history. Even after 350 years, new information emerges. For example, a recently discovered document from 1680, attesting to Jan P. Haring’s inheritance of his brother’s estate in the Netherlands, raises fresh questions about his background, education, and motivations. A historian’s work, like history itself, is never done.

Adapted from a New Amsterdam History Center program at Arader Gallery in New York City on October 6, 2024.